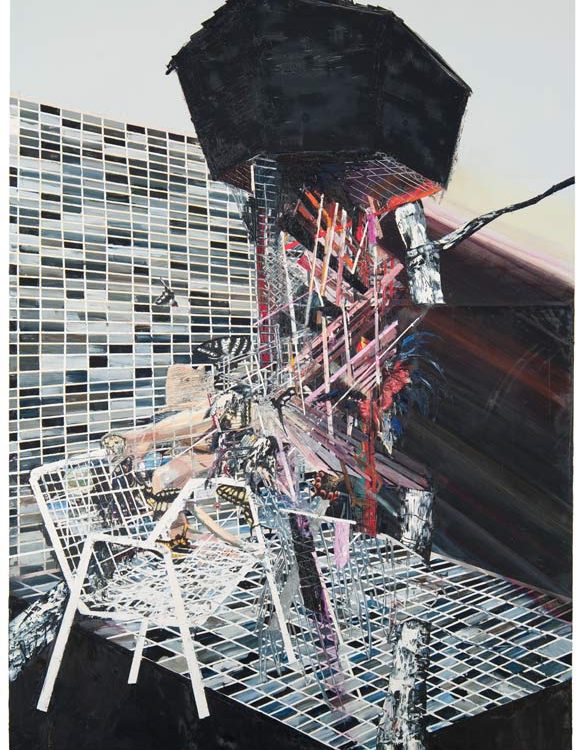

vanishing points: paint and paintings from the debra and dennis scholl collection

Featuring paintings from the collection of Debra and Dennis Scholl, Vanishing Points is an exhibition that explores how we perceive painting today as it relates to the history and continued viability of the medium. The exhibition presents three viewpoints: Sweeping Horizontality and Aerial Views, The Painterly without Paintings, and Impossible Task. Sweeping Horizontality and Aerial Views analyzes paintings that present stretched perspectives and linear structures that are often associated with cinema. The Painterly without Paintings describes the extreme edge where the medium of painting itself vanishes. That is, where color leaves the canvas behind without divesting itself of the painterly. Operating as a third vanishing point, Impossible Task, examines the “impossible” phenomenon of paintings that unravel Western perceptions of cosmological and idiosyncratic order.

Knight Curatorial Fellow Kristin Korolowicz interviews vanishing points guest curator Gean Moreno. Miami-based writer and artist Gean Moreno is founder of [NAME] Publications, a platform for book-based projects and a contributing editor of Art Papers magazine.

Kristin Korolowicz: So, how did this show come about? Perhaps you can talk about your selection process from the collection and your decision to organize a painting show.

Gean Moreno: Previous exhibitions of works from the Scholl’s collection have centered around photography and more recently sculpture. I think that the general perception is that the collection is made up of a certain kind of stage-set photography produced at the end of the 1990s. However, a recent exhibition at the Frost Museum that showcased the sculptures in the collection revealed that this isn’t the case at all. While the earliest portions of the collection may coincide with the emergence of a certain type of photography, it has grown in other directions in the last ten years. The sculpture show included works that ranged from Robert Morris to Trisha Donnelly, displaying a historical and aesthetic breadth that I believe is present throughout the entire collection. One of my goals in this exhibition was to show the presence of this diversity in the collection’s paintings.

KK: What type of range did you notice?

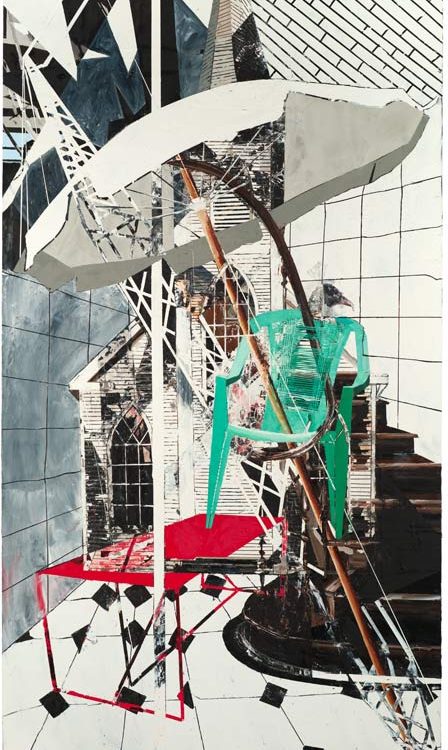

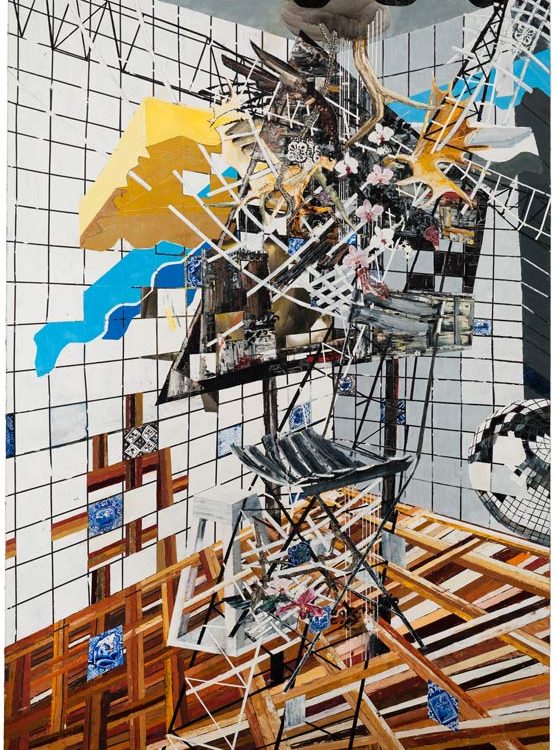

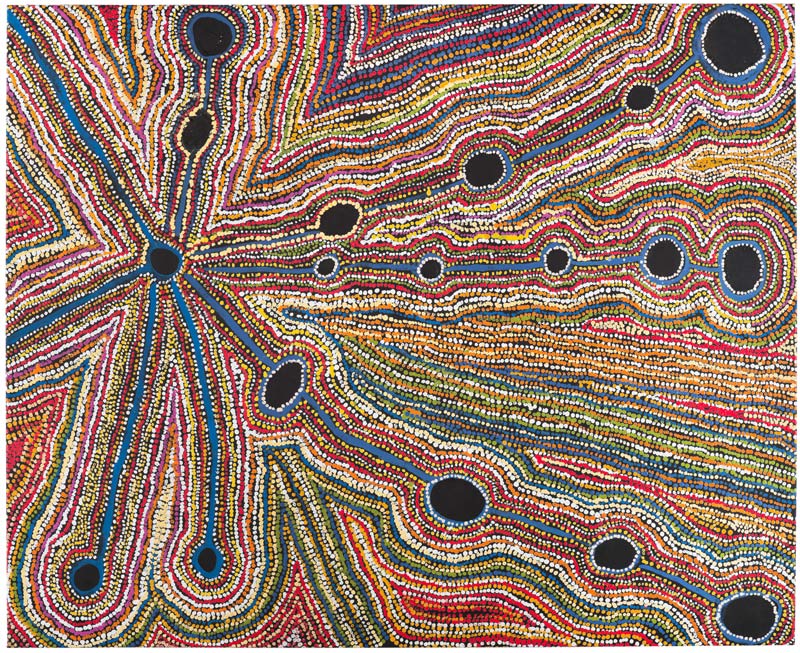

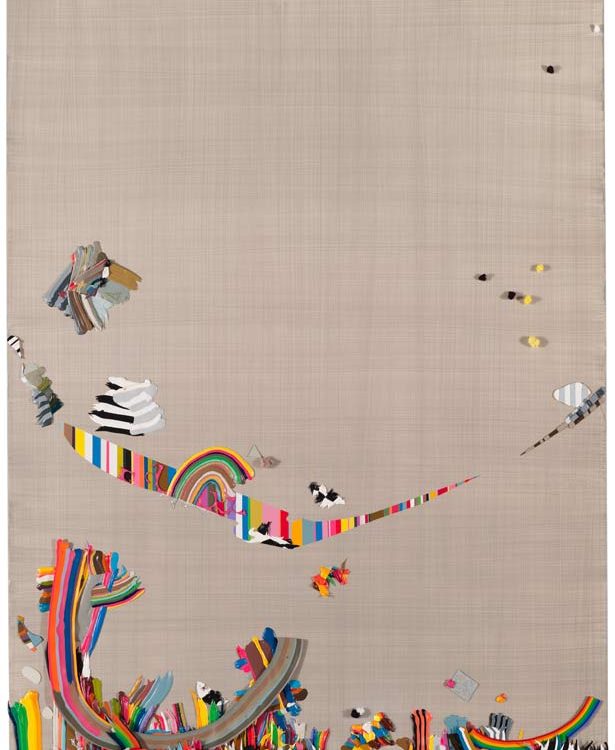

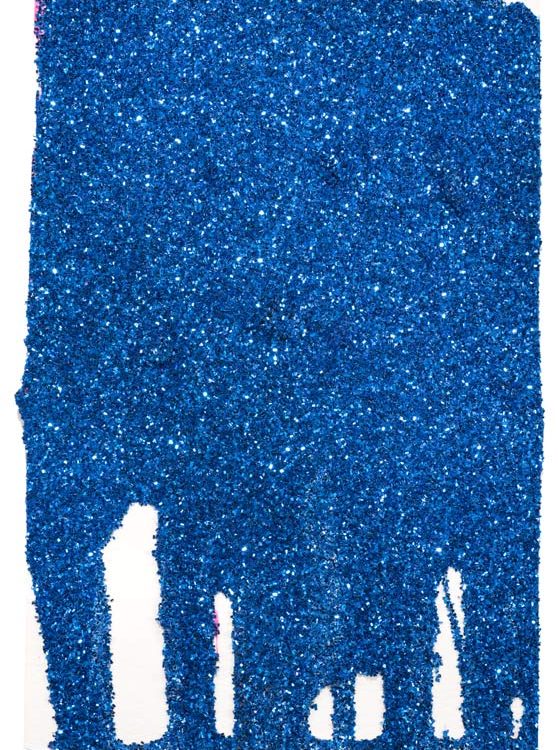

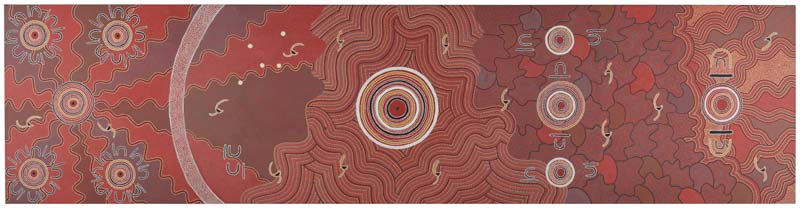

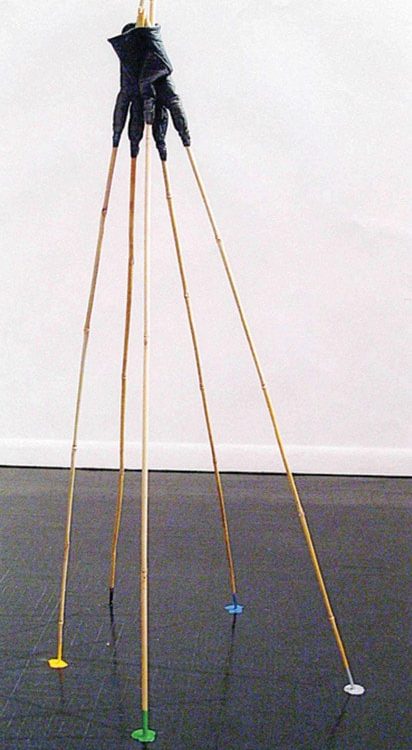

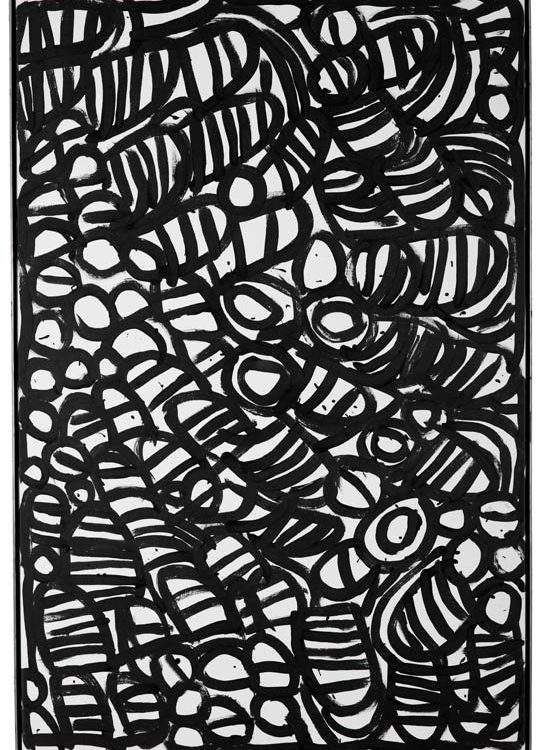

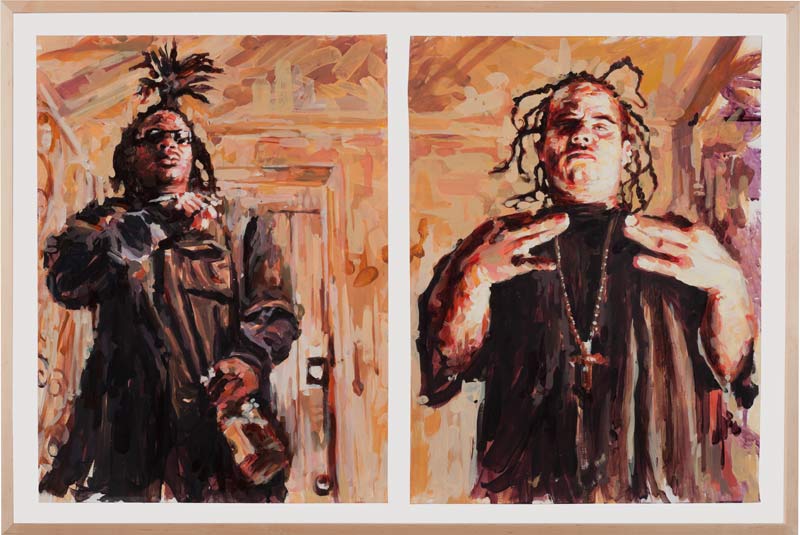

GM: Artists in the collection range from Mark Bradford, who works in an urban environment with city detritus, to young Miami painters, to artists who leave the canvas altogether behind, like Jim Lambie and Sylvie Fleury. The collection even features Australian Aborigine dream paintings.

KK: What will be the anchoring works of the show?

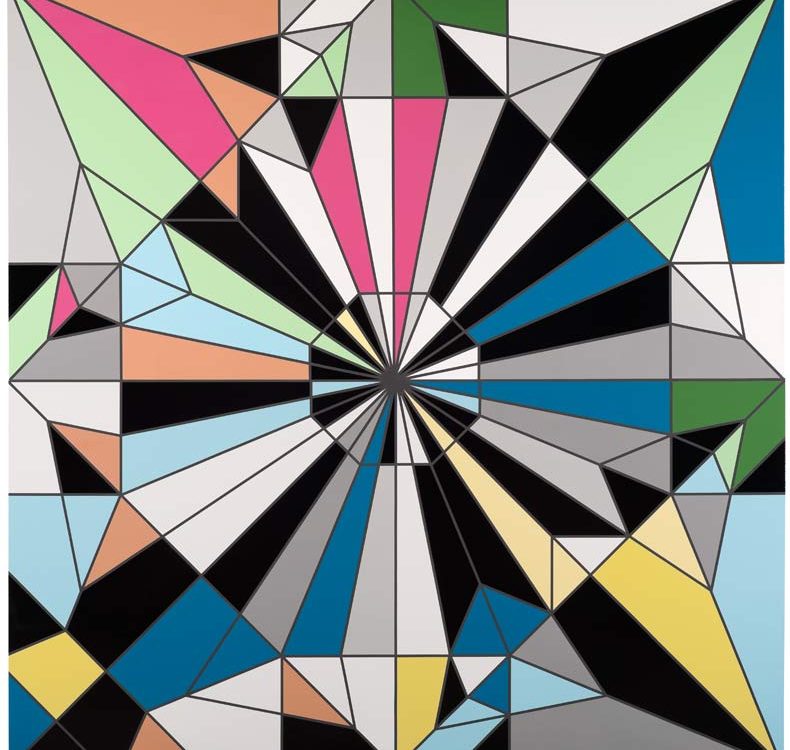

GM: The position of Jim Lambie’s Zobop at the entrance of the exhibition and museum will give it great visual presence and will be a good introduction. Sylvie Fleury’s piece will also be impactful. I suspect that the most interesting aspect of the show will be the sparks that flare between paintings in the gallery space. One such point of contention will likely be a room that includes works by Carla Klein, Mark Bradford, and Sarah Morris—all large paintings facing off.

KK: On that note, can you briefly describe the exhibition’s themes/narratives and how you arrived at them?

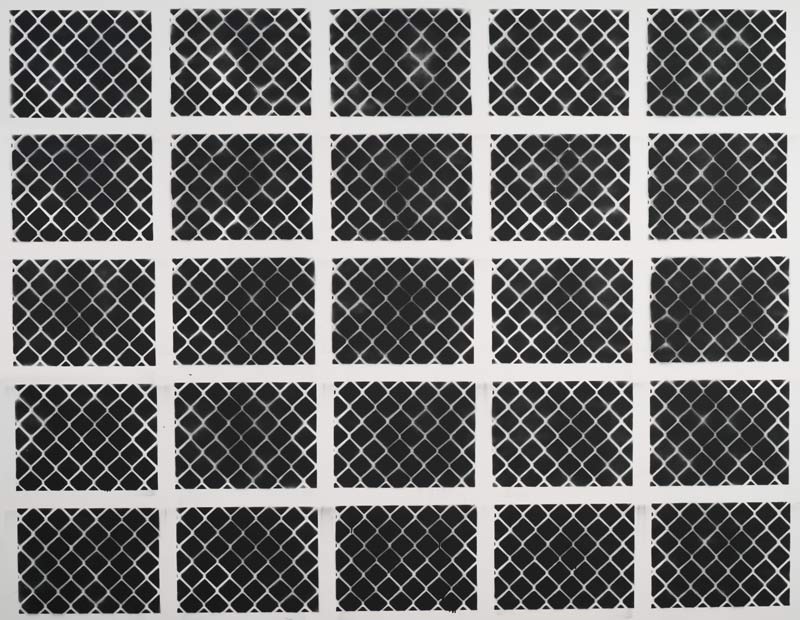

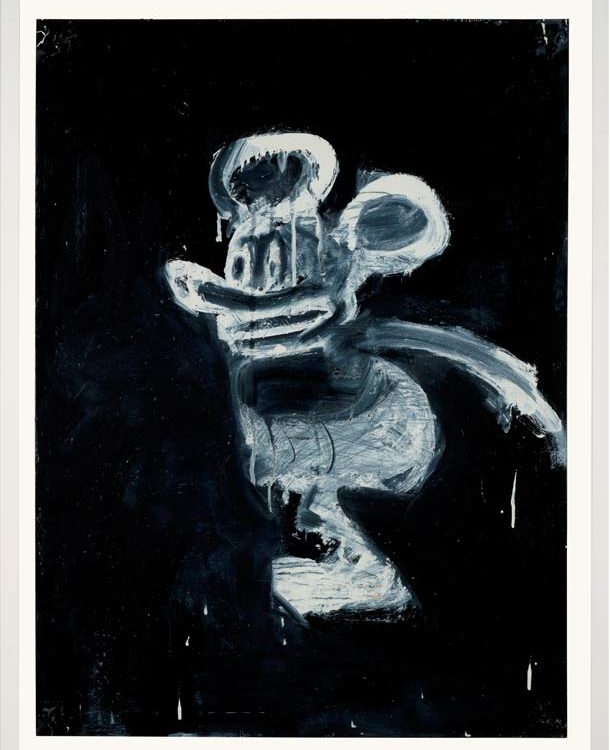

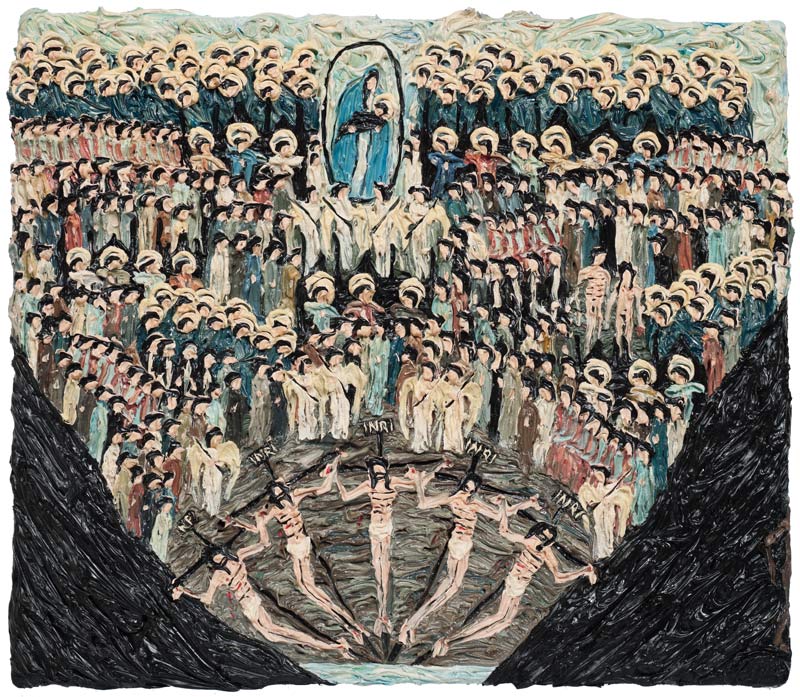

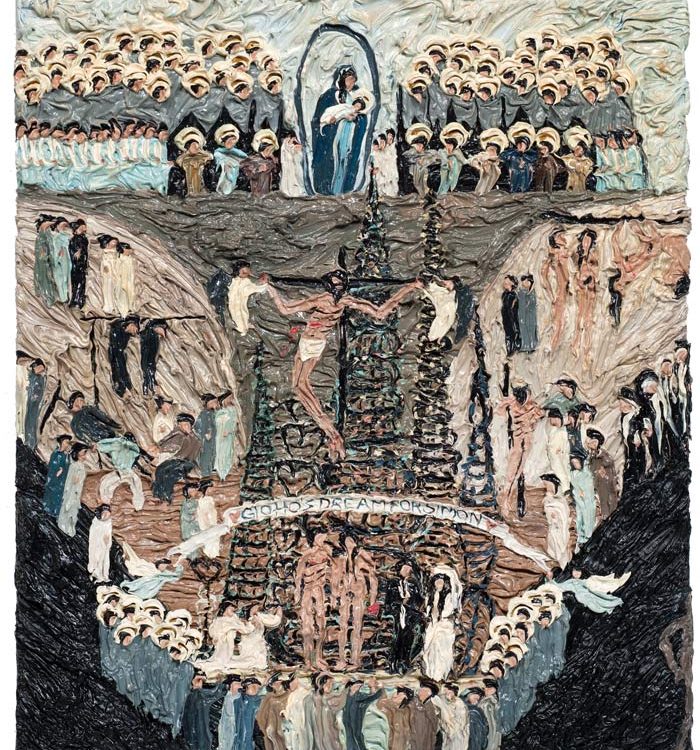

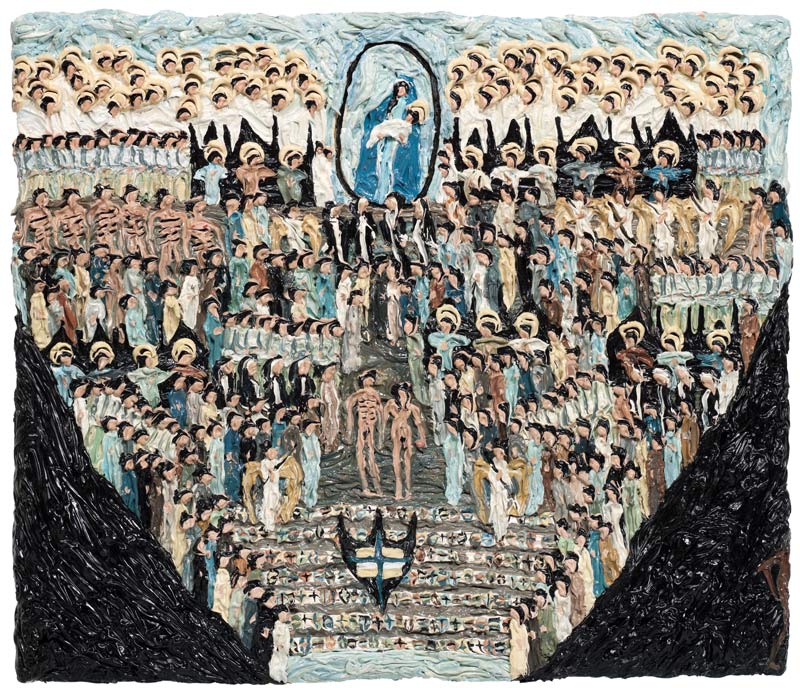

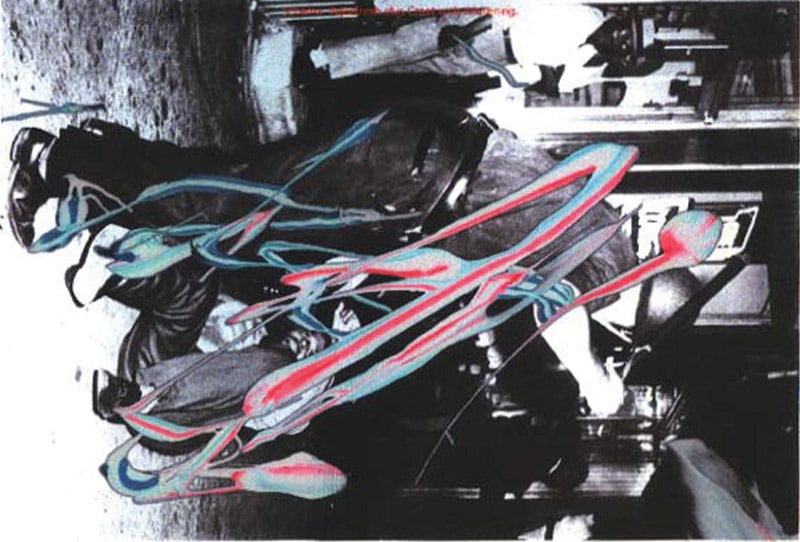

GM: I’m structuring the exhibition as three concurrent storylines that never meet, much like a movie with three narrative strands that unfold concurrently but aren’t neatly brought together at the end. The three overarching storylines emerged naturally from my selection of paintings. One storyline revolves around the notion of perspective. If traditional perspective embodies the geometric rationality that prevailed during the Renaissance, then what form of perspective represents our current mathematical, physical, and social understanding of the world? This particular storyline asks whether fractured architectures or geometric aerial views are good answers to the question of perspective in the present day. This section will include the elongated perspectives of Carla Klein and the “aerial” views of Mark Bradford and Sarah Morris. The second storyline is concerned with what happens when painting is invested with immense “cosmovisions” or with logics of intense personal desire. How does a painting deal with the Afro-Caribbean culture that Jose Bedia attempts to insert into it? How do Aboriginal dream paintings function when presented with painting’s necessarily limited representational range? Finally, the third storyline looks at what happens when a painting leaves the canvas behind. This group will include objects like Jim Lambie’s tape-covered ramp and Sylvie Fleury’s smashed hot pink car.

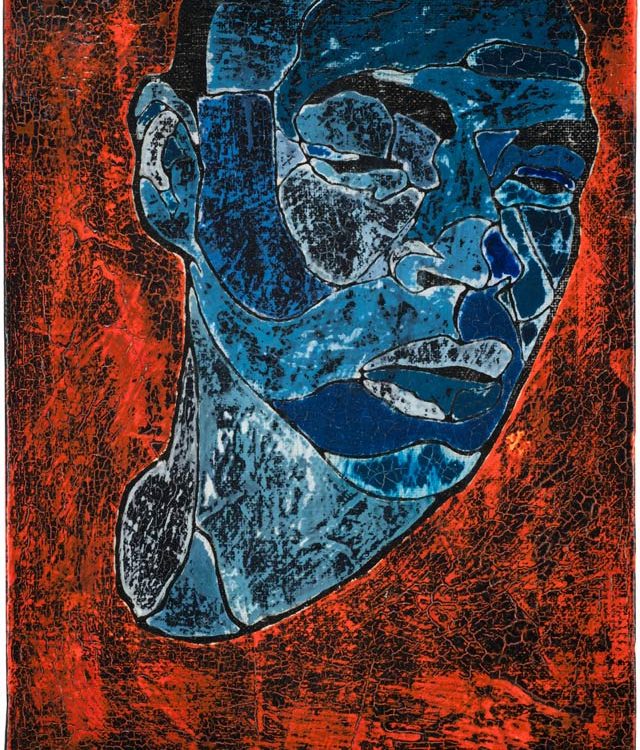

KK: Can you explain to us what a “cosmovision” is? And can you talk more specifically about the “logics of intense personal desire”? Is this something you see particularly in Jose Bedia’s work, or are you speaking in more general terms?

GM: A cosmovision is a spiritual or religious understanding of the world/cosmos. For instance, we can talk about a Yoruba cosmovision or a Christian cosmovision, an exclusively Yoruba or Christian understanding of the world. In Bedia’s case we can speak of an Afro-Caribbean cosmovision. In this show, I seek to illustrate the difficulty, if not the impossibility of capturing on canvas the complex human perspectives embodied in a cosmovision. Artists are presented with a similar, but opposite problem; this is where desire comes in. Just as a cosmovision is too broad to be easily captured in a painting and is restrained by the limits of the medium, an artist’s vision may be bound by the limits presented by their own desire. Painting becomes a challenge for artists not because of the immensity of their vision, but because of the tightly bound space of their desire.

KK: As we’re on the topic of perspective and/or ways to understand the world, what is your interest in the notion of a vanishing point? And how do you see this notion relating to the exhibition?

GM: A vanishing point is one of the elements that help organize traditional perspective. I’m using it in an ironic way, proposing that the very idea of perspective, and the world that invited us to imagine it, is vanishing. Contemporary physics and new representational technologies, from satellite imagery to cellular modeling, invite us to imagine a different kind of world and different symbolic forms for it. Richard Sarafian’s movie, Vanishing Point (1971), accepts this invitation in a fascinating way. The movie’s plot is very simple, almost simplistic: someone has to transport a car from the middle of the US to the West Coast in an absurdly short period of time. What is most interesting is that a number of shots in the film illustrate massive highway systems in the desert. It’s as if the single-point perspective of the protagonist has been replaced by sweeping views that more aptly describe a world flattened by immense infrastructural spreads.

KK: I think it’s telling that you mention film. The way you’ve organized the show borrows from a type of cinematographic perspective, which appears to have informed your approach to these works. This moves in the direction of my next question: the perspective storyline and expanded field of painting storyline have a strong relationship. However, I’d like to know what relationship you see between the spirituality storyline and the other two. I know you mentioned before that they never meet, but I’m interested in hearing more about the space they share.

GM: I see the exhibition as a triptych, as three storylines that never meet. Certain films—and certain novels—unfold along multiple narrative lines. The expectation is that these different stories will meet at the end and some important thing about the way in which they are connected will be revealed. However, some films adopt another method: it’s not some final moment of unity that allows different stories to exist side-by-side, but a thematic redundancy between them that holds the movie together. Dusan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie is a good example of this, as is Antonioni/Wenders’ Beyond the Clouds. Like the separate plots in these films, I think that the three unconnected storylines in the exhibition are held together by a thematic redundancy. This redundancy can be found in the “areas of competence” presented by the paintings. This concept comes from Greenberg, but I think I’m using it in a broader way by asking what a painting is good at and at what point painting slips into an incompetent mode of expression. This comes back to your question about Bedia and cosmovisions. I think that by infusing painting with this massive Afro-Caribbean cosmovision he challenges painting’s competence in being able to represent spiritual values.

KK: So, in other words, you are saying that painting slips over into an incompetent mode when it fails to represent particular symbolic forms and values. Do you see this as something potentially generative in the way that it tends to question the ability to represent or communicate these forms within painting?

GM: Yes, I think the idea of incompetence arises at a point at which paintings meet a certain resistance. I think it is totally generative. It is what keeps painting active or activated, what keeps it from settling into adequate modes—which means into a kind of standardization and repetition. Incompetence should be thought of here not as a lack, as when we say such-and-such is incompetent at his or her job, but in terms of projection. Perhaps a painting isn’t supposed to be capable of completing its task, but instead captures something and opens new spaces in the attempt.

KK: You’ve described this exhibition before as exploring “the equivocal meaning of the notion of the vanishing point and how it relates to history and continued viability of painting…” What are your thoughts on the viability of painting today?

GM: In relation to this exhibition, I think that we can speak of painting as still providing symbolic forms for an understanding of things/the world that has been evolving at an incredible speed in the last thirty years. And this of course may involve the very inability to produce “proper” symbolic forms. In more general terms, and perhaps in a more political mood, I think that painting may still open a space in which we can deal with the contradictions of a culture propelled exclusively by the exigencies of the bottom-line.

Gean Moreno is a writer and artist based in Miami. He has contributed texts to various catalogues and anthologies, including Uncertain States of America! (Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo), Round-Leather Worlds (Martin Gropius-Bau, Berlin), Catastrophy? What Catastrophe!? (Quebec Biennial), 2009 e-flux Reader (Sternberg Press, New York), Eat the Frame! (DFI Publishers, Amsterdam), Statements of Necessity (Alonso Art, Miami), and Peter Friedl (Extra City, Antwerp). He is currently contributing editor of Art Papers magazine, and has published in e-flux journal, Monu-A Magazine for Urbanism, Flash Art, Art Nexus, and ArtUS. His work has recently been exhibited at the North Miami MoCA, Kunsthaus Palais Thum and Taxis in Bregenz, Institute of Visual Arts in Milwaukee, Haifa Museum in Israel, Arndt & Partner in Zurich, and Invisible-Exports in New York. In 2008, he founded [NAME] Publications, a platform for book-based projects. He is adjunct professor at Florida Atlantic University.